Ethena's Custodian Moat

Or how to win the stablecoin wars.

NOTE: This post is part 5 of a multi-essay effort to understand Ethena from first principles. Many people have asked me to write a take on Ethena but truth be told I don't know how it works. Each week I will cover a concept that will help me get closer to breaking down the synthetic dollar protocol. This post is focused on Ethena’s Architecture and USDe moats. The previous post in the series is here.

Thanks to Figue for offering feedback on the premise.

Since SUSDe (Staked USDe) yields dropped to 11% (just 6% over USDY yield), Ethena’s not been a popular topic.

The opening is over.

Into the middle game we go.

Most of the retail opportunity is gone so the speculators are looking elsewhere but the protocol builders are watching intently as the battle for stablecoin dominance truly begins.

If you followed the previous posts in this series, we finally understand enough about derivatives markets to succinctly explain Ethena, its rise and potential to continue growing its share of the stablecoin market.

Ethena is a tokenized cash-and-carry strategy

Technically USCC (introduced a week ago) is much closer to this in its marketing, a tokenized cash-and-carry fund for institutional investors.

But Ethena is doing the same exact thing, creating a synthetic dollar as a byproduct.

Cash-and-carry strategies exploit arbitrage in situations where a long futures contract is relatively expensive (in high demand) and therefore a trader can use a long position of the asset as collateral to obtain a short position in the futures contract.

Here’s how it works when minting USDe:

The minter puts up $1 worth of stETH (or equivalents)

The protocol uses the stETH as collateral and obtains a short perpetual position that perfectly offsets the ETH exposure from one of the whitelisted custodian exchanges

Not only does the staked ETH position generate staking yield, the short perp position receives a positive funding rate. as ETH vs. USD perpetuals have a positive market sentiment

Ethena then passes most of this yield on to stakers (SUSDe holders)

Here’s a simple diagram from Luca Prosperi:

For more details and charts on how this trade works mathematically, see the previous post in the series.

Consider this similar reductive take also from Luca Prosperi:

Interestingly, SUSDe holders (effectively the junior tranche?) do not carry slashing risk.

Instead, their main downside is lowered access to liquidity and $ENA rewards?

A quick clarification on Luna

With this framing we can settle an important debate.

About 4 months ago, when Ethena still had 30% yields, the prevailing question was to what extent the yields are unsustainable and whether it could lead to a Luna-style collapse.

As a tokenized strategy backed by a growing insurance fund Ethena clearly carries its own risks, for example:

Smart contract risks with any dependencies or Ethena itself

Loss of staking yields or even slashing

Issues with custodians

Persistent negative funding rate if market sentiment changes

And so on.

Any risk that can affect the cash-and-carry trade will apply to USDe also.

But that in itself doesn't imply similarity with Luna.

There’s no such thing as a risk-free stablecoin.

The issue with Luna was that its yield was recursively tied to its token appreciation.

Ethena’s yield is simply tied to the profitability of the underlying trade (with some additional tweaks driven by the decision to stake).

And the trade is built to arbitrage the combination of inflationary USD and deflationary ETH.

As a result, Ethena’s yields have come down while its supply has continued to grow, now exceeding $3B.

Winning the stablecoin market

Our primary question is always how protocols acquire market power.

I haven't thought about the competitive dynamics of issuers at any length so I studied both Guy Young’s recent talks as well as Arthur Hayes' 2nd Nakamo Dollar post Dust on Crust Part Deux which leave some useful clues.

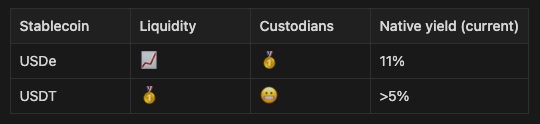

In short, stablecoins have three moats:

Liquidity, which ensures easy conversion to-and-from the most important risk-on crypto assets like ETH. Liquidity is strongly affected by both the issuance capacity and level of integration in the ecosystem. This is a reflection of how stablecoins are currently used and could shift over time to payments and reserves which we de-emphasize here;

Custodians, which looks at the diversity and risks associated with the venues where the stablecoin protocol holds its reserves. This is also an important input to overall strategy capacity.

Native yield. Revenue is not usually a moat but since stablecoins often focus on a specific asset class, the native yield of that asset class is an important strategic input. The native yield of the asset class determines long-term differential profits. This is a form of counter-positioning.

Arthur Hayes points out that Tether's flaw is in its reliance on only one US-domiciled custodian bank to support very attractive profits and he believes it could delist Tether.

Instead, Ethena had two clever ideas:

Rely on centralized perps exchanges as custodians providing for much higher strategy capacity (missed by previous attempts to tokenize cash-and-carry like USDL);

Enshrine them on its cap table, making it hard for a competing product to replicate the trade (which is remarkably simple both from an execution and smart contract point of view).

This is a classic “cornered resource”.

The other mechanisms, such as whether revenues are internalized or distributed to users (stakers), token mechanics, the level of yield vs. risk and others are very helpful from a go-to-market perspective (perhaps essential to unseat Tether’s liquidity advantages?) but not crucial in predicting the level of market power attainable.

Fun homework if you'd like to take this further: use it to evaluate USDM.